Acknowledging Those Beyond the Scope of the Database:

A Collective Biography

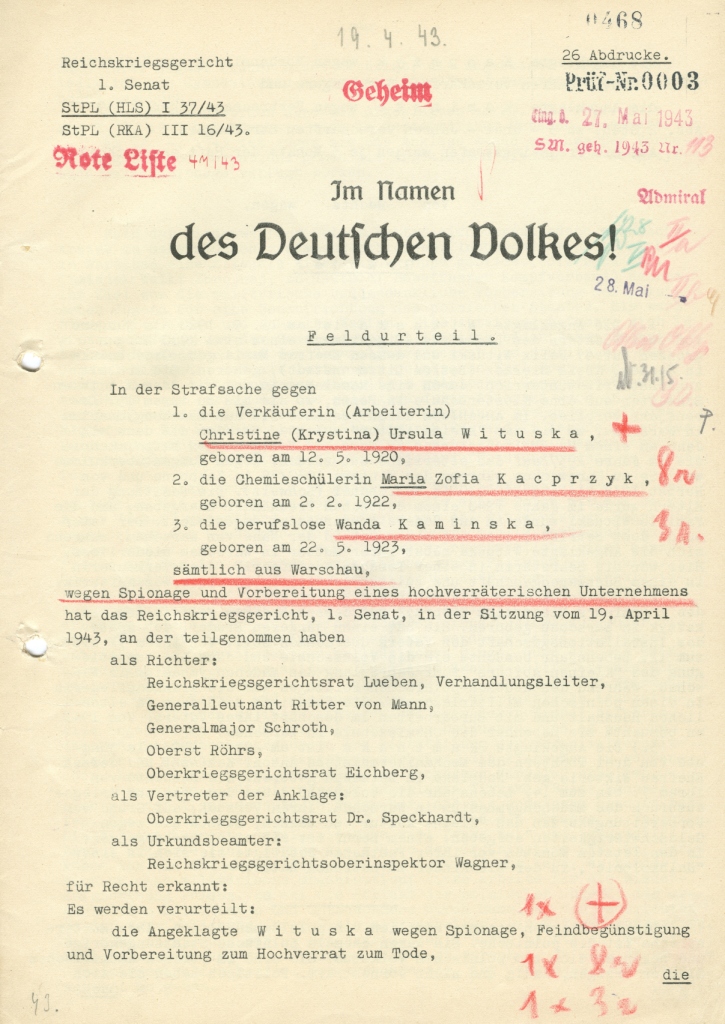

Krystyna Wituska

born in 1920 near Łódź, Poland

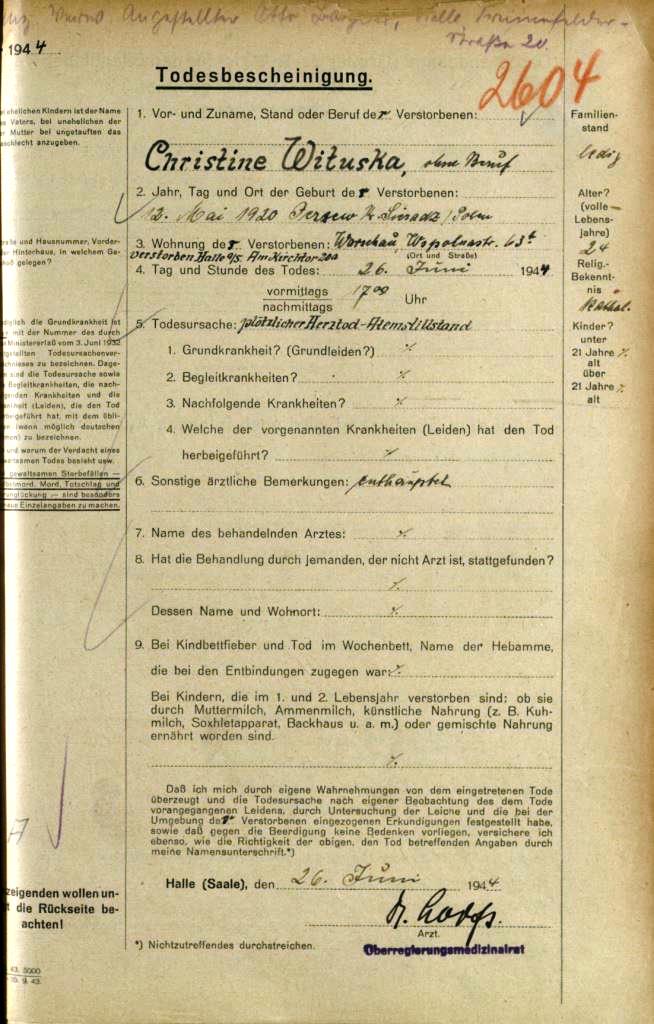

died in 1944 in Halle (Saale), Germany

Krystyna Wituska was born on May 12, 1920, near Łódź, Poland. She attended a convent school in

Poznań and later a high school in Warsaw. Just a few months after the German Wehrmacht invaded

Poland, her family was dispossessed and deported to the part of Poland referred to as the

"General Government." From then on, Krystyna Wituska worked as a secretary and sales assistant

in Warsaw. There, she reconnected with a school friend from Poznań who was active in the Polish

resistance organization "Union of Armed Struggle" (Związek Walki Zbrojnej, ZWZ), the

intelligence service of the Polish Home Army (

After being instructed in the structure and organization of the Wehrmacht, she attempted to gather information about German military units through acquaintances with German soldiers. Like other members of her group, she met soldiers at the café "Club," a place in central Warsaw reserved for Germans, and observed military barracks. For these espionage activities, the Gestapo arrested Krystyna Wituska along with other female resistance fighters in October 1942.

In February 1943, Krystyna Wituska and fellow ZWZ member Maria Kacprzyk were transferred to the Berlin-Moabit detention center. From July 1943 onward, they shared a cell with Helena Dobrzycka, who had been arrested for courier work.

The three women communicated with other prisoners through the window and exchanged secret messages. In their cell, they were assigned sewing tasks but also used the machines for personal purposes, crafting gifts.

Through an unusual friendship with guard Hedwig Grimpe, they maintained contact with the outside world. A pen-pal relationship also developed with Grimpe’s daughter, Helga. Following Krystyna Wituska’s instructions, Helga created an album in which she preserved the letters her mother smuggled out of prison. Hedwig Grimpe also provided the Polish women with extra food, medicine, and cigarettes – despite the high personal risk this entailed.

While the Reichskriegsgericht (Reich Court-Martial), the highest military court of the Wehrmacht, sentenced Maria Kacprzyk and Helena Dobrzycka to prison camp and they survived the war, it sentenced Krystyna Wituska to death in April 1943 for espionage and preparation of high treason.

In October 1943, she was transferred to Halle and beheaded on June 26, 1944, in the "Roter Ochse" prison. The Anatomical Institute of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg received her body for teaching purposes. Her remains were likely cremated and buried in the Gertrauden Cemetery, though documentation has not survived. A memorial stele with her image has stood in the institute’s burial plot since 2014. The memorial commemorates not only Krystyna Wituska but also 69 other individuals whose bodies were handed over to the anatomical institute after execution at the "Roter Ochse." Krystyna Wituska gives these people visibility.

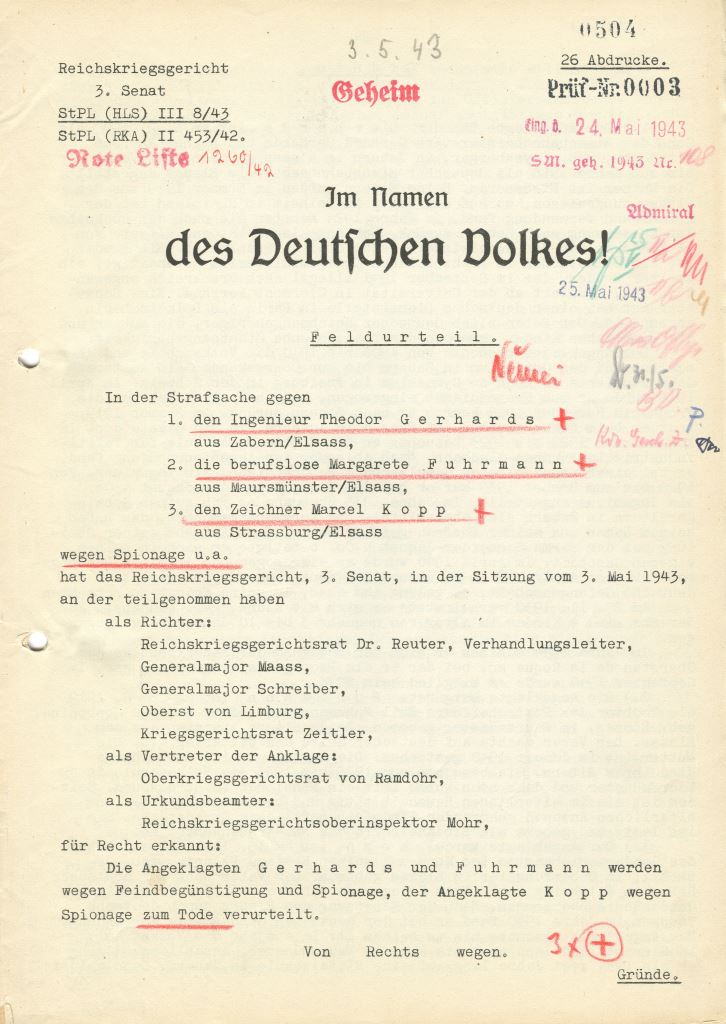

Théodore Gerhards

born in 1900 in Saverne (Zabern), then part of the German Empire (Alsace-Lorraine), today France

died in 1943 in Halle (Saale), Germany

Théodore Gerhards was born on February 1, 1900, in Saverne (Zabern), a town in Alsace-Lorraine annexed by the German Empire in 1871. As a result, he was a German citizen by force, though raised as a Frenchman, and had to serve in the Imperial German Army at the end of World War I. After returning home and serving in the French army, Théodore Gerhards obtained French citizenship, trained as an engineer, and worked as a sales representative. In the 1930s, the father of four gave up this work to support his wife in running a grocery store.

Just a few months after the German Wehrmacht occupied France in the summer of 1940, Théodore Gerhards joined the Resistance. He led a network that hid escaped French prisoners of war, provided them with food and false papers, and helped them cross into the unoccupied zone of France. The network also gathered intelligence on war-related industries in Alsace.

After being betrayed by the organist of the parish in Saverne – with the help of a maid working in the Gerhards household – the Gestapo arrested Théodore Gerhards on July 6, 1942. After a short detention in Strasbourg and weeks of interrogation in Kehl, he was transferred to Berlin in late November for trial before the Reichskriegsgericht (Reich Court-Martial). On May 3, 1943, Théodore Gerhards and two co-defendants were sentenced to death for aiding the enemy and espionage. After Hitler rejected a clemency appeal, the court transferred him to the prison in Halle, where the sentence was carried out on October 29, 1943.

Initially, Théodore Gerhards' body was taken by the Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. It was cremated shortly afterward, and the urn was interred at the Gertrauden Cemetery in Halle. In 1948, a French reburial commission returned the urn to Saverne. When Théodore Gerhards' widow Claire was buried in 1999, only the lid of the urn was found – the family kept it as a memento.

Soon after the war, French authorities began prosecuting collaborators and Gestapo informants. In 1946, a court in Saverne sentenced those who betrayed Théodore Gerhards to death or life-long forced labour. At the family's request, the death sentence was not carried out and was commuted to a prison term.

Théodore Gerhards' resistance efforts have been honoured several times in France. On November 22, 1946, General Jacques-Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque awarded the Resistance Medal to Théodore Gerhards' seven-year-old son, Maurice, who accepted it on behalf of his executed father. Since 1980, a street in Saverne has been named after Théodore Gerhards.

Rudolf Bertram

born in 1908 in Hundisburg, Germany

died in 1943 in Halle (Saale), Germany

Rudolf Bertram was born on August 28, 1908, in Hundisburg (Haldensleben district). After finishing school, he initially worked in agriculture. From 1937 onward, he was employed by the Reichsbahn (German National Railway). He and his wife, whom he married in 1929, had four children.

In 1942, a group of rail yard workers in Magdeburg-Rothensee, including Rudolf Bertram, committed thefts during working hours. According to the court ruling, Rudolf Bertram was involved in 18 such incidents. The stolen items included shoes, clothing, cigarettes, and cheese. In ten cases, he was also charged with receiving stolen goods.

The Sondergericht (Special Court) in Magdeburg sentenced Rudolf Bertram to death in March 1943 under the so-called "Verordnung gegen Volksschädlinge" (Decree Against Public Enemies), which allowed the death penalty even for minor offenses. The court emphasized that the crimes "were committed by exploiting wartime conditions."

Since the sentence was imposed by a Special Court, it became final immediately – Rudolf Bertram had no right of appeal. His wife submitted a clemency petition, requesting not to enforce the judgement. Statements from various authorities acknowledged mitigating factors: Rudolf Bertram had confessed, expressed remorse, had no prior convictions, and enjoyed a good reputation.

The judiciary, however, emphasized that as late as August 1942, another 24 shunting workers had been convicted of theft by the Special Court in Magdeburg; this had been known to Rudolf Bertram. The court apparently saw the need for an even harsher penalty in his case to deter others. The Reich Ministry of Justice rejected the clemency petition.

Rudolf Bertram was executed by guillotine on May 3, 1943, in the prison in Halle. His body was handed over to the Anatomical Institute at the University of Jena. There, most of the bodies of executed persons were used for studying the muscular system. However, no such notation exists in Rudolf Bertram's case. It is unclear how long his body remained at the institute, when it was cremated, and where it was buried. No gravesite remains.

Unfortunately, no portrait or other photographs of Rudolf Bertram have been available in a quality suitable for publication.

This collective biography was written by Gedenkstätte ROTER OCHSE, Halle (Saale).

© 2025 by Gedenkstätte ROTER OCHSE, licensed under

CC BY 4.0