Irmgard Dörr

born in 1924 in Berlin, Germany

died in 1940 in Brandenburg, Germany

“Aunt Illig, Aunt Illig, they want to kill me.” This sentence appears in a nurse’s note from February 1938 in the medical records of Irmgard Dörr.

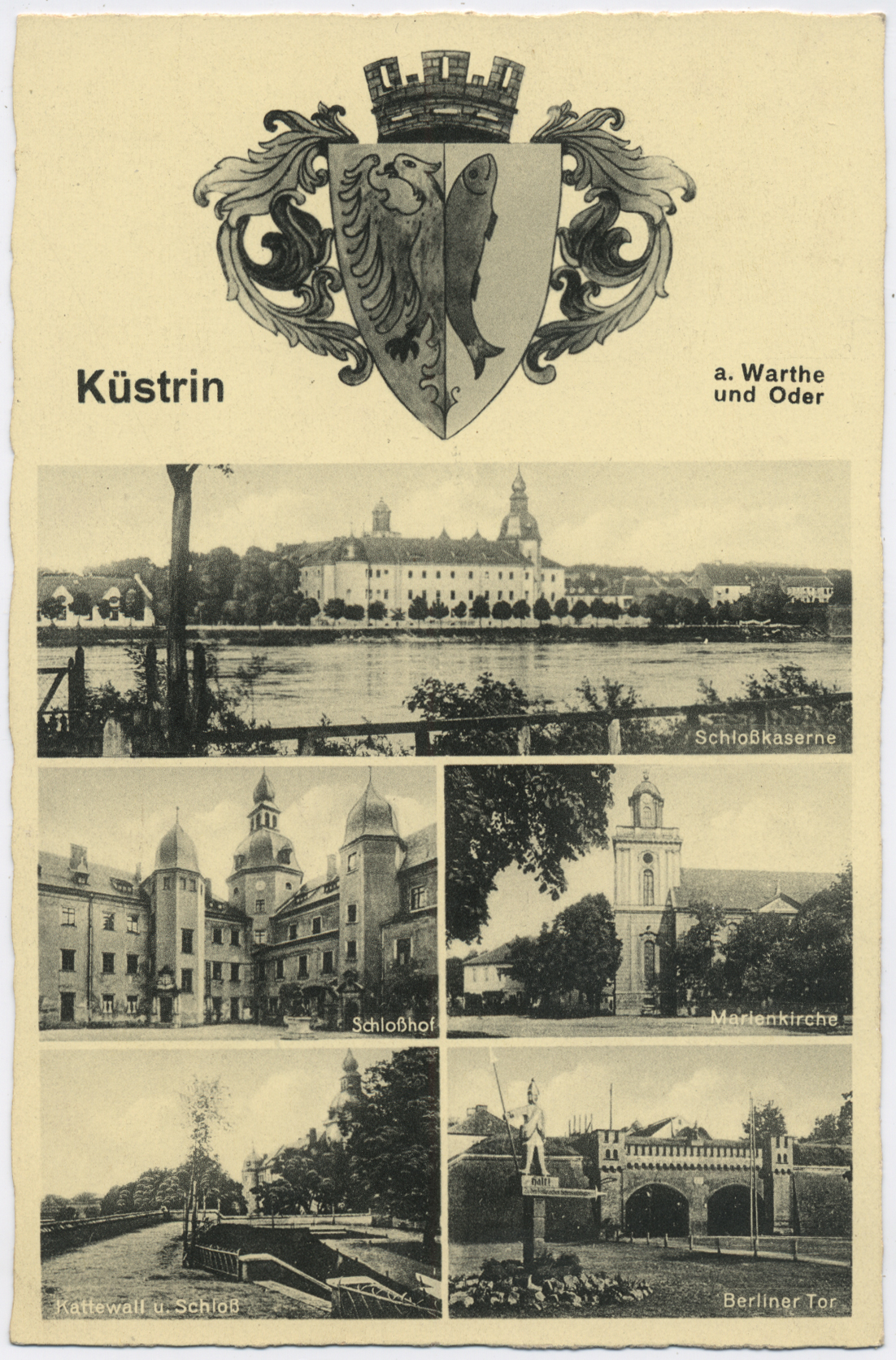

She was born in Berlin in 1924 and grew up in Küstrin on the banks of the Oder River, likely as one of seven children. According to a municipal welfare worker’s note in the files, Irmgard Dörr and her brother were born out of wedlock and were both considered intellectually disabled. Their father, according to records, had been an alcoholic and had died of tuberculosis.

However, Irmgard Dörr did not live with her mother either. She had been placed in several foster homes through the Berlin orphanage until the age of four. After that, she repeatedly moved back and forth between her biological mother – who later married a labourer and had five more children – and various foster families.

In 1931, the district court of Küstrin withdrew custody from the mother, as Irmgard Dörr and her brother were considered neglected and uncared for in comparison to the legitimate children. It is possible that they were also physically abused, as suggested by a question Irmgard Dörr asked during a medical examination, recorded by the city physician: “Do you hit?”

Irmgard Dörr was enrolled in a Hilfsschule, a remedial school for children with intellectual disabilities common at the time. She was regarded there as a “troublemaker.” Between August 1932 and Easter 1935, she did not attend school; her compulsory education was suspended on the grounds that she was considered “uneducable” due to her diagnosed intellectual impairment.

The child spent three more years with a foster family, before she – in need of institutional care – was admitted to the Landesanstalt (state institution) in Potsdam. According to the medical intake questionnaire, the foster mother had refused to continue caring for Irmgard Dörr. She was said to have had fits of rage without apparent cause, accompanied by the destruction of surrounding objects, behavior which had worsened in the months leading up to her institutionalization. In March 1934, the municipal welfare worker also reported that the child engaged in self-stimulation, which was classified as “pathological or abnormal.”

The medical records from the Potsdam institution contain detailed entries about Irmgard Dörr, which reflect the apparent strong interest in her “case.” She was described as very fearful. During bathing, she apparently expressed fear of drowning, and when observing other children getting their hair cut, she was afraid their ears would be cut off.

In her anxiety, she repeatedly asked the adults around her the same questions: “Is that a woman? Is the bird a human? Is the mouse a human?” However, the doctors and caregivers noted that Irmgard Dörr seemed to be “more gifted than her performance indicated” (entry from November 6, 1934). She was very interested in the people around her and demonstrated great skill in certain tasks, such as packing collected items.

Her desire for ownership was especially strong. It may have been precisely this discrepancy between her evident abilities and her designation as intellectually impaired that made her appear particularly interesting. She also showed a capacity for joy and curiosity, wanting to explore what was happening in the examination and treatment rooms.

According to the reports, Irmgard Dörr preferred to play alone rather than with other children. She was very focused on her own activities, refused tasks assigned to her in the ward (such as polishing brass), and showed no interest in schoolwork. She responded poorly to admonitions and was said to lack any sense of shame or disgust. However, she learned melodies and Christmas songs quickly and sang them correctly.

She appeared to have had a bond with her last foster mother and was happy to receive gifts and greetings from her, though she never visited. Over time, Irmgard Dörr’s fearfulness subsided, and during walks, she began to ask complete strangers questions. She wished for a doll’s pram for Christmas and was very interested in having her hair done nicely – she distinguished people around her by their hairstyles.

In January 1935, the eleven-year-old began attending the preparatory class at the institution’s school. While she appeared to enjoy going to this school, her medical records indicate that this was primarily due to peripheral aspects such as the morning “flag parade” and the breakfast provided. She learned to count to ten using her fingers and was able to write, though with frequent errors. The educational shortcomings were attributed to Irmgard Dörr herself and explained by her alleged “laziness” in completing schoolwork. An intelligence test administered in 1937 determined an intellectual age of only 6.7 years for the thirteen-year-old, largely ascribed to substantial deficits in general knowledge. In October 1937, she was removed from school due to what was described as “poor academic performance.”

A “neurological examination” by the institutional physician Friederike Pusch (1905–1980) followed, along with a diphtheria vaccination and serological-bacteriological tests, all of which yielded no pathological findings.

In early November 1937, the state institution in Potsdam submitted an application for Irmgard Dörr’s sterilization on the grounds of a severe intellectual disability. The Hereditary Health Court (Erbgesundheitsgericht) in Potsdam approved the sterilization request after a hearing on February 25, 1938, at the district courthouse on Lindenstraße, where the court claimed to identify signs of intellectual impairment in Irmgard Dörr, who was present.

As Irmgard Dörr grew older, she was described less as a child and more as someone to be evaluated for her work capacity and productivity. Her occasional self-talk was increasingly interpreted psychiatrically and classified as hallucinations: “Irmgard was walking peacefully beside me. Suddenly she grabbed her head with both hands, ran forward screaming, and cried louder and louder, ‘Aunt Illig, Aunt Illig, they want to kill me’” (entry from February 21, 1938).

What was presented here as evidence of a psychosis turned out to be a cruelly accurate perception of reality during her further stay in the institution. It also occurred just four days before her hearing at the Erbgesundheitsgericht. It can be assumed that Irmgard Dörr, who had already been given an “Information Sheet on Sterilization” (a signed copy is in her medical file), was intensely preoccupied with the consequences of the impending invasive procedure.

The forced sterilization was not carried out until October 1938. Possibly, the delay was due to the transfer of the children's ward and its residents from Potsdam to Görden (a district of Brandenburg an der Havel), which, in Irmgard’s case, took place on September 5, 1938.

Since summer 1938, Irmgard worked in the Schälküche (“peeling kitchen”), but her performance was assessed as low. The district welfare association, which was responsible for covering the costs, inquired whether, based on positive reports, a placement in a more affordable educational home might now be possible. Friederike Pusch, the institution′s physician, rejected this, pointing to Irmgard Dörr’s supposedly continued need for institutional care.

In Görden, entries in her medical file were made only once a year. These noted no significant changes. Irmgard Dörr apparently sought “friendship” with nurses but was not reciprocated. She continued to have little contact with other young people in the ward and increasingly talked to herself. A “Form 1” (Meldebogen 1) was completed for her, diagnosing a “childhood psychosis (mood swings, states of agitation, negativism, withdrawal)” and an intellectual disability. As a result, the 16-year-old was deemed unfit for any employment. On October 20, 1940, a final summary of her medical case listed all of her supposed deficits, emphasizing especially that she would “lose herself in her own trains of thought” and ask “completely confused and unrelatable questions.” Irmgard Dörr was considered difficult.

On October 28, 1940, she was transferred – along with nearly 60 other children and adolescents – to the Tötungsanstalt (killing center) Brandenburg and murdered by gassing. Irmgard Dörr’s brain was dissected after the murder, without any pathological findings. The preserved specimen was listed among those buried at Munich’s Waldfriedhof (Forest cemetery) in 1990.

This biography was written by Uwe Kaminsky.

© 2025 by Uwe Kaminsky, licensed under

CC BY 4.0

Sources:

Bundesarchiv / Federal Archives Berlin, R 179/3994