Dr Jakub Beatus

born 1873 in Kalisz, Russia

died 1940 in Warsaw, Poland

Childhood and Youth

Jakub Beatus was born on 1 September 1873 to a Polish Jewish family in Kalisz. His parents were Joachim Beatus and Dorota née Łaska. His father owned a chemist’s store in the city centre.

Before the First World War, Kalisz belonged to the Russian Empire and was located near the border with Germany. In August 1914, most of the historical old town was destroyed by German bombardment. In 1918, Kalisz became part of independent Poland, and Jews made up more than 30% of the city’s population.

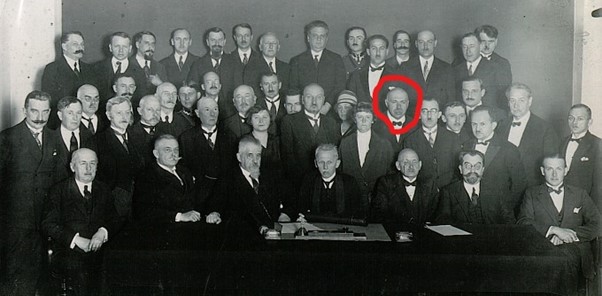

From 1882 to 1890 Jakub Beatus attended a philological gymnasium in Kalisz. He obtained a medical degree in 1896 and initially settled in the town of Koło. In 1902 he returned to Kalisz and found temporary work in the Jewish Hospital, where he assisted in surgeries and treated outpatients. He was later employed as a physician in the local prison. After the First World War, Jakub Beatus opened a private practice as a dermatologist and venereologist. He worked at same time for the Social Insurance Institution. Jakub Beatus was a member of the Kalisz Medical Society, and he was also active in the Kalisz Society for the Support of Poor Jews as well as the “Drop of Milk” charity, which provided pasteurised milk and medical care for infants from working-class families. On the eve of the Second World War, Jakub Beatus lived in a house at Rzeźnicza 2, near the southern corner of the Main Town Square in Kalisz.

Persecution and Death

After the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, Kalisz was annexed to Nazi Germany as part of the Reichsgau Wartheland. In December 1939, the Nazis brutally expelled 10,000 Jews to the General Government, forcing the remaining Jews to flee in panic. Jakub Beatus managed to escape to Warsaw in January 1940, but his younger sister Teofila was murdered by the Nazis outside of Kalisz.

Meanwhile, sanitary conditions in Warsaw had deteriorated as a result of German bombardment, which cut off the city’s water supply, damaged many hospitals and destroyed 12% of all residential buildings. The ensuing public health crisis was augmented by the arrival of 90,000 destitute Jewish refugees who had either escaped from Nazi persecution in smaller towns in Central Poland or had been expelled overnight from areas in the north and west of Poland that were annexed to the German Reich.

Makeshift refugee shelters were opened in schools, synagogues, and private flats, often inside huge tenement houses in the densely populated northern district of Warsaw. These refugee shelters were extremely overcrowded and often lacked heating, running water, and basic sanitary appliances. They soon became breeding grounds for typhus (Fleckfieber in German), a potentially lethal infectious disease spread by body lice.

When a typhus epidemic broke out in Warsaw in late 1939, Dr Beatus found work as a physician in the refugee shelters. Tragically, while attending to the sick, he fell ill himself. He was admitted to the Czyste Jewish Hospital, where he was diagnosed with typhus complicated by bronchopneumonia. He died on 21 March 1940, only one day after admission, but a death certificate was never issued.

After the war, based on an inaccurate witness testimony, the Municipal Court in Kalisz declared his date of death to be 31 December 1942.

Postmortem Use of Specimens

The brain of Dr Beatus was extracted during an autopsy and, in April 1940, was sent by German military pathologists to Professor Julius Hallervorden (1862–1965) at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Brain Research in Berlin-Buch. Hallervorden must have been aware that specimen M-51 came from a Jewish physician in occupied Warsaw, as it was labelled “Dr Beatus” in the inventory of his collection of supposedly “military” brains.

During the Second World War, together with another neuroscientist Bernhard Patzig (1890–1958), Hallervorden directed the Military Medical Academy’s Special Unit for Research into War Damages to the Central Nervous System. He collected more than 1,500 “military cases” (specimens supplied by German army pathologists), including 165 brains of people who died of epidemic typhus in German-occupied Warsaw. Typhus was virtually unknown in pre-war Germany, and Hallervorden was interested in this disease because of the characteristic changes it causes in the brain. Hallervorden and his supervisor, Hugo Spatz (1888–1969), later boasted that they had amassed the largest collection of “typhus brains” in the world.

Tissue sections derived from the brain of Dr Jakub Beatus were retained after 1945 by the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research. In the mid-1960s, they were still stored in the institute’s old building in Frankfurt am Main. In the early 1980s, the brain samples were most probably discarded because they were no longer regarded as scientifically relevant.

This biography was written by Michał Palacz.

© 2025 by Michał Palacz, licensed under

CC BY 4.0