Józef Bażak

born 1911 in Juszczyn near Maków Podhalański

died 1941 in Munich

Childhood and Youth

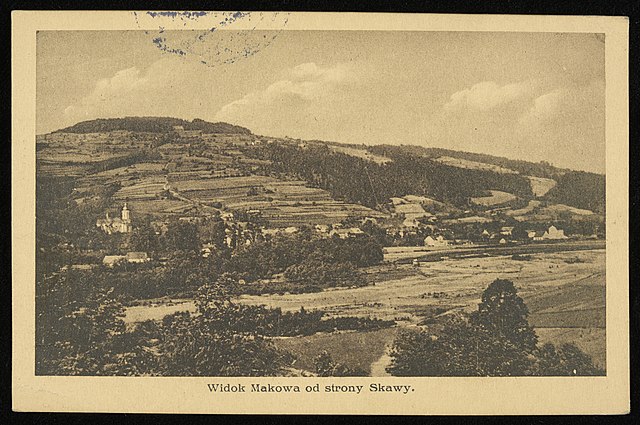

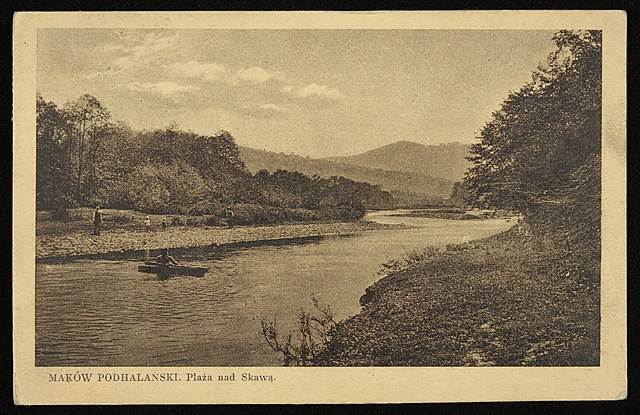

Józef Bażak was born on 21 June 1911 in Juszczyn, a village near Maków Podhalański located along the River Skawa in the Western Beskid Mountains. This region had been under the rule of the Habsburg monarchy since the First Partition of Poland in 1772 and was mostly populated by the Górale, also known as Polish Highlanders.

Following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, the area became part of independent Poland. Józef Bażak completed 3 years of primary school education. He got married in 1937 and had two children. The family owned a small farm in the nearby village of Grzechynia.

Persecution and Death

After the German occupation of Poland in September 1939, the whole area became part of the Cracow District in the General Government. In March 1940, Józef Bażak was recruited for forced labour in Germany and, from Easter 1940, worked on a farm in Haunreut near Passau in Lower Bavaria. Józef Bażak was regarded by his employer as a diligent worker. According to sources, he became increasingly agitated and wanted to go back to Poland after he had received several letters from his wife threatening suicide and urging him to return home.

Reconstructing the events from this point onward is difficult due to the fragmented and often contradictory source material. The available information comes from witness statements, police reports, and court records, but in most cases, the original documents have not been preserved. Instead, only summaries or translations exist, such as those found in forensic psychiatric evaluations or records of the Munich prosecution office.

The statements attributed to Józef Bażak in perpetrator sources further complicate the picture. If these documents were taken at face value, his accounts would seem to change over time, making it difficult to determine what really happened.

Supposedly, after he had not received any letters from his wife for three weeks, Józef Bażak started having dreams and hearing voices that told him that his wife had murdered their children and run off with another man. Other voices allegedly told him that the police from Passau would come for him and cut his head off.

On 24 May 1940, Józef Bażak was beaten up by his employer and supposedly attempted to commit suicide by jumping into a pond. He ran away from the farm the following night and hid in the forest for a couple of days. Józef Bażak was arrested on 27 May 1940 for abandoning his workplace and taken to the Gendarmerie station in Fürstenzell. While trying to escape from jail, he apparently stabbed a German policeman with a sharpened rifle cleaning rod.

The circumstances surrounding the death of the policeman are particularly puzzling. According to trial records, Józef Bażak found a rifle cleaning rod under his bed, sharpened it by rubbing it against the wall, and then used it to attack the officer when he opened the cell door. However, this account raises doubts – why would such an object be in a prison cell in the first place? The only undisputed fact is that the policeman suffered a fatal stab wound to the abdomen. Beyond that, what really happened remains unknown. Józef Bażak was charged with murder and detained in Passau.

In June 1940, he was transferred to the notorious Munich-Stadelheim Prison. His behaviour was described as extremely agitated, restless, confused and aggressive and, according to sources, he had to be artificially fed through a tube. He was considered unfit to stand trial due to suspected mental illness and was sent for psychiatric observation to the Psychiatric Clinic of the University of Munich.

He soon calmed down, started to eat normally, and gained weight from 46 to 53 kg (he was 163 cm tall), but according to reports from nurses, he seemed to be searching for a way to escape from the hospital. During his examination in the psychiatric clinic, several old injuries were discovered, but it is unclear whether these injuries were inflicted before or during arrest. He had an old fracture in the left forearm that required treatment with a splint and numerous old wounds on the head that were apparently caused by cutting weapons. According to hospital records, Józef Bażak broke his right forearm and was hit on the head after he attacked a prison guard in Stadelheim with a bucket. The psychiatric evaluation was hindered by the fact that Józef Bażak did not speak any German and had to be examined with the help of an interpreter.

Dr. Vult Ziehen (1899–1975), an assistant in the clinic and NSDAP member since 1932, wrote an expert opinion for the prosecution. He found it more probable that Józef Bażak was simulating a mental illness called “prison psychosis”, but he did not exclude the possibility that he suffered from schizophrenia. Ziehen concluded that there remained doubt over Józef Bażak’s penal responsibility for the crime. However, the Special Court in Munich concurred with the other expert witnesses, Dr. Rudolf Engler (b. 1894) from Passau and Dr. Heinrich Vogler (b. 1886) from Stadelheim. Both opined that Józef Bażak was definitely simulating a “prison psychosis” in order to escape punishment.

In November 1940, Józef Bażak was found guilty of manslaughter as well as crimes against the 1939 Ordinance against Criminals Employing Violence and the Law on the Protection of Legal Order and Peace of 1933. He was therefore sentenced to death based on Hitler’s decrees that introduced draconian punishments for violent crimes. Before 1933, the maximum punishment for manslaughter was life imprisonment, and even death sentences for murder were often commuted to a prison sentence. Józef Bażak was moreover tried by a Special Court (Sondergericht ), a type of court that was reintroduced by the Nazis in 1933 and followed a summary procedure that severely limited the rights of the defendant and did not provide the possibility of appeal.

On 14 January 1941, at 6:20 am, Józef Bażak was beheaded with a guillotine in Munich-Stadelheim Prison by the Bavarian state executioner Johann Reichhart (1893–1972). According to the official protocol, the condemned man resisted the cutting off of his head with shouting and wailing. After the death sentence was carried out, posters announcing the execution were displayed for three days in Munich, Passau and Fürstenzell.

Józef Bażak’s wife was not notified about her husband’s death and was not given an opportunity to claim his body.

Postmortem Use of Specimens

Józef Bażak’s corpse and his severed head were therefore handed over to representatives of the Anatomical Institute of the University of Munich. Józef Bażak’s brain was removed and immediately sent to Professor Willibald Scholz (1889–1971) from the Brain Pathology Department of the German Institute for Psychiatric Research (Kaiser Wilhelm Institute) in Munich. The fresh brain was dissected and fixed in alcohol. 24 tissue sections were later extracted for the purpose of a histological examination. The preserved brain autopsy report reveals that Willibald Scholz found evidence of slight lymphocytic infiltrates and cerebellar cortical damage in Józef Bażak’s brain. Scientific discoveries from the 1990s suggest that damage to the cerebellum might explain psychotic symptoms in some patients. This supports the argument that, on account of a mental disorder, Józef Bażak should not have faced penal responsibility for manslaughter.

After the war, the specimens were retained as objects of scientific interest by the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry (MPIP). His death sentence was reviewed in 1989 by a legal adviser of the Max Planck Society who found this to be an ambivalent case and recommended separate burial at the Waldfriedhof (forest cemetery) in Munich. However, this recommendation was not implemented, and all 24 tissue sections derived from Józef Bażak’s brain remained in the possession of the MPIP.

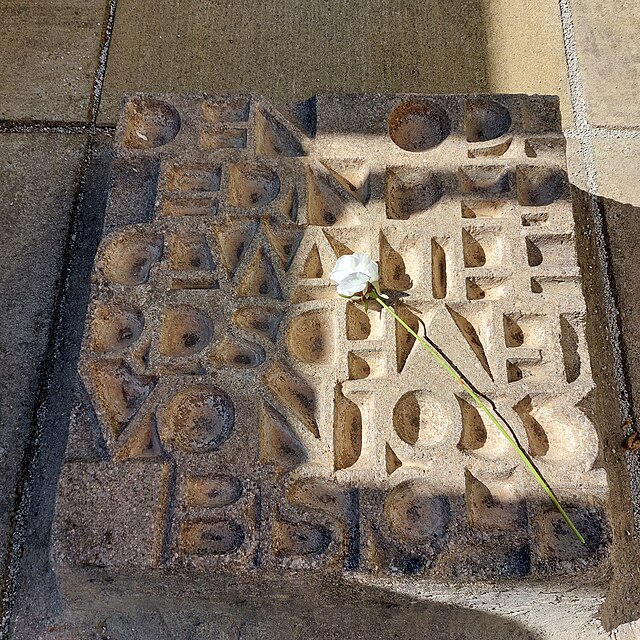

At the conclusion of the current provenance project, the specimens will be buried at the Waldfriedhof, and Józef Bażak will be commemorated along with other victims of unethical brain research in Nazi Germany.

This biography was written by Michał Palacz.

© 2025 by Michał Palacz, licensed under

CC BY 4.0