Meta Bärwolf

born 1875 in Dachwig, Germany

died 1943 in Hildburghausen, Germany

On February 10, 1941, Meta Bärwolf, who had been living at the Landesheil- und Pflegeanstalt (State Sanatorium and Care Facility) in Hildburghausen, Thuringia, since early 1927, wrote a letter to the institution's director, Johannes Schottky (1902–1992), in which she asked him for a conversation:

"Dear Director Schottky, Please forgive me for once again allowing myself to address a few lines to you today. […] As early as November 16, 1940, I handed a letter addressed to you to Miss Dr. Bucher for forwarding. I hope it has reached you. Even then, I asked you for your valuable advice and help, and I would like to do so again today. Thank God, I now feel well again and have a great joy in working, not only in the musical field. As I already told you […], I attended the Fürstliches Conservatorium für Musik [Royal Conservatory of Music] in Sondershausen for four years […] and also taught there, in addition to giving many private lessons in piano and violin. Noble music was and still is a source of joy and recreation, it gives my life a higher value. I no longer have great expectations of life, but – I hope you can understand this – I would like, after my release from this sanatorium, to find housing and an environment in which I can feel comfortable. I would like to ask you, dear Director Schottky, for the promised meeting, so I can talk about this matter, which is very important to me. Would you be so kind as to help me find a field of activity that suits me? […] I have confidence in you and know that my request is not in vain. With heartfelt greetings, I remain yours in gratitude, Meta Bärwolf (Music Teacher)"

Meta Bärwolf's letter, which is preserved in her medical file, reflects the central theme of her stay in Hildburghausen. She wanted to leave the psychiatric institution as soon as possible and return to her old, long past, but familiar life.

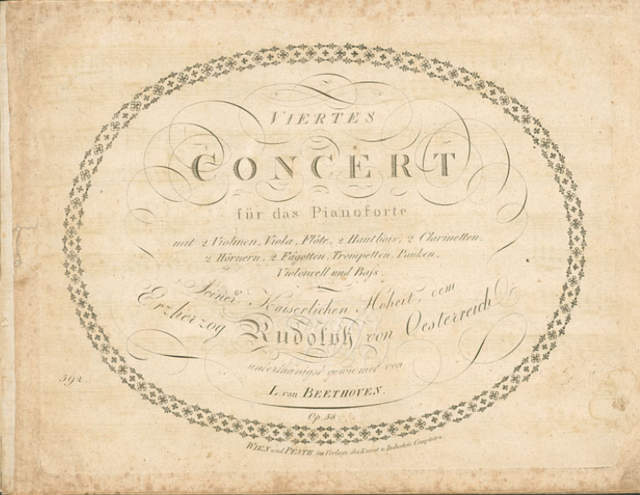

Meta Bärwolf was born on December 20, 1875, as daughter of master carpenter Carl Bärwolf and his wife Karoline, née Alband. Born in Dachwig near Erfurt, she and her family soon moved to Sondershausen, where she attended the Höhere Mädchenschule (a type of secondary school for girls from upper class families). Starting in the spring of 1886, she attended the aforementioned conservatory, a musical training institution that, under its founding director Carl Schroeder (1848–1935), would shape the reputation of Sondershausen as a music city for years to come. Her years at the conservatory were the most exciting and formative time of her life. Her major was piano, and her minor was violin. In addition, she completed required courses in harmony, methodology, music history, and choral singing. In 1896, Meta Bärwolf passed her final exams. A highlight of this period was her performance with the famous Loh Orchestra. She played Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 and received favourable reviews. She subsequently gave music lessons for many years. Meta Bärwolf lived a withdrawn life, was deeply devoted to her profession, and worked diligently.

She experienced her first life crisis after the death of her father from colon cancer in 1908. This was not the first stroke of fate for the family. Her mother Karoline also succumbed to cancer, though the exact date of her death could not be determined from available sources. Meta Bärwolf had three brothers, two of whom died at a young age. Her third brother later died of tuberculosis. Her father's death hit her hard. She wept often and became very agitated. Her mental state continued to deteriorate, leading to her admission in May 1909 to the University Psychiatric Clinic in Jena, where she remained for nine months.

After her release, Meta Bärwolf immediately resumed work as a teacher of piano and violin. To pursue her profession, she rented a room at Hauptstraße 56 in Sondershausen. Her parents had also lived in this house, which was owned by the Jewish Heilbrun family, who operated their textile goods business there. One member of the family, Carl Heilbrun, advised Meta Bärwolf in financial matters. He was later appointed as her legal guardian during her stay in the Hildburghausen institution, a role he fulfilled until his emigration to the United States in 1936.

During the course of 1926, Meta Bärwolf's mental health deteriorated again to the point that she was readmitted to the University Psychiatric Clinic in Jena in April. Ten months later, she was transferred to the Landesheil- und Pflegeanstalt Hildburghausen. At her new place of residence, the 51-year-old Meta Bärwolf soon confided in a female physician. She told her, she had always lived only for her music and "had known no greater purpose in life than harmonizing with young students and bringing joy to all people." But suddenly she had been overcome by fear of what would become of her. She should not have had to worry about the future – she had saved some money, had reliable insurance, and a circle of good friends – yet she "couldn’t shake the fear." Things apparently got worse, to the point that she could hardly concentrate or motivate herself to do anything.

Meta Bärwolf was never to leave the Hildburghausen institution again before her death in November 1943. For a long time, as her medical file suggests, the doctors and nurses seemed genuinely concerned with her physical and emotional well-being and took an interest in her as a person. She was regularly allowed to play music. Most often, Meta Bärwolf played piano in the women’s ward, the so-called "Villa II." This gave her great joy, as she wrote in a letter to relatives on October 15, 1938: "I play piano daily in Villa II, glorious works of our masters Beethoven, Wagner, Liszt, Grieg, Chopin, Schubert, etc., for my own and many others’ enjoyment." Occasionally, she was even allowed to perform in front of a larger audience in the Georgenhalle located on the institution' grounds. There, she presented her "hallenging pieces from memory, in excellent fashion."

On selected days, Meta Bärwolf also visited elderly ladies of Hildburghausen's upper class. She played music with them or gave them private concerts. One of these "dear friends," as Meta Bärwolf called them, was Clara Nonne (b. 1856), the sister of influential Hamburg neurologist Max Nonne (1861–1959). These outings were a welcome break from institutional routine. Meta Bärwolf looked forward to them for days in advance, especially because she could briefly interact with members of the "feinere Gesellschaft" (high society) – a milieu to which she felt she belonged.

Even when she wasn’t playing herself, almost everything in Meta Bärwolf's life revolved around music. In her free time, she read biographies of famous musicians or copied sheet music with great joy. In the evenings, she would sit near the radio and listen attentively to classical music, later enthusiastically recounting which compositions she had heard and when and where she had performed them herself. Besides music, Meta Bärwolf maintained an "enormous correspondence" with her relatives, friends, and former students from her Sondershausen days. The tone of her letters was always the same: "I want to return to Sondershausen; I want to resume my profession as a piano teacher."

Her yearning to return home and to her old profession is unsurprising when one considers her daily life at the Hildburghausen institution beyond her musical pursuits. Her daily routine included work in the sewing room. Meta Bärwolf spent nine hours a day knitting cardigans "from unraveled yarn" – a task she found monotonous, nerve-wracking, and exhausting. Nevertheless, she carried out her work diligently and was considered a rather industrious worker over a long period.

Doctors and caregivers at Hildburghausen described Meta Bärwolf as "emotionally unstable." Phases of orderliness, friendliness, and even charm alternated with agitated episodes in which she was apparently perceived as irritable, difficult, and contentious, often leading to disputes with fellow patients. She characterized herself – rightly so – as a "free spirit" who "hated all coercion." With such a mindset, difficulties in an authoritarian and rigid institution like Hildburghausen were inevitable. Her constant and forceful requests to play piano, write letters, and be discharged immediately tested the patience of the staff. Rarely did the personnel show as much understanding as suggested by a note from her medical file dated January 1, 1937: "The patient is visibly suffering inwardly; her constantly agitated state, if it continues, raises concerns about her heart." Usually, however, the staff reacted harshly, sometimes with draconian measures: temporary transfers to a different ward without a piano, being confined to bed for days, regular administration of sedatives, or prolonged baths were used to manage the restless patient.

Overall, the staff's attitude toward Meta Bärwolf was ambivalent. Harsh punishments for disobedient behaviour alternated with surprising freedoms granted during calmer periods. One could say: from the staff's perspective, Meta Bärwolf was surely a demanding and exhausting patient – but one whose virtuosity at the piano also fascinated.

This view is also reflected, at least in part, in the response of institution director Johannes Schottky to the letter cited at the beginning, which Meta Bärwolf had written to him in February 1941. Schottky, a radical racial hygienist and staunch supporter of the Nazi patient murders, actually explored the possibility of discharging Meta Bärwolf from the institution in the time that followed. A letter from him to Simon Steffan dated March 13, 1941, has been preserved. Steffan, a senior inspector by profession, residing in Erfurt and related to Meta Bärwolf, had previously indicated a willingness to take her in if her condition allowed it. That condition was now met, Schottky wrote: "Miss B.[ärwolf] is calm, peaceful, able to care for herself entirely. For her age, she is still remarkably fit and can be engaged in simple tasks such as darning, needlework, and light housework."

In the end, she was never released. Meta Bärwolf was to remain in Hildburghausen for the rest of her life, where she had repeated conflicts with fellow patients. According to her medical records, Meta Bärwolf was mainly to blame. It was repeatedly noted that she considered herself superior and made that known to those around her. On December 10, 1941, it was recorded: "She still has difficulty integrating into the community. She boasts about her good education and the titles of her acquaintances. She claims she doesn't belong among such common people. (…) She likes to play the virtuous old lady."

Indeed, she found it very unpleasant when others discussed romantic entanglements or sexual desires. According to her own account, Meta Bärwolf never cared much for men.

It is possible that Meta Bärwolf harboured a certain sense of social superiority. But her conflicts with others can also be interpreted differently. She missed conversations about the things that mattered to her and made her happy. She loved talking about art and culture – and she missed her home. A prime example of this is a letter she wrote on April 15, 1943, to the retired teacher Rosa Seidler from Sondershausen. Right at the beginning, she wrote that she wanted to "chat a little with dear good Miss Seidler" –about Sondershausen and music. Clearly, there were too few people in the Hildburghausen institution who wanted to talk to her about these things.

The overall picture outlined above began to change fundamentally in the fall of 1943. On October 20, Meta Bärwolf was transferred to a ward for restless patients because she had for a while been considered "very disruptive." Five days later, she had to undergo electroshock therapy. Over 15 days, four sessions were carried out in which 300 to 400 milliamperes of direct current were passed through her brain. This form of treatment was not unusual in Hildburghausen, which saw itself as a modern therapy centre. In a letter to the Thuringian Ministry of the Interior dated February 1944, Schottky stated that Hildburghausen now offered "all modern treatment methods (insulin therapy, sleep cures, hormone therapy, electroshock therapy, fever therapy, etc.)."

Ultimately, Johannes Schottky must be seen as a typical representative of psychiatry in the Nazi era, which is aptly summarized by the concept of "heilen und vernichten" ("healing and annihilating"). Reform and murder were not mutually exclusive – they were two sides of the same coin. In order to focus on treating those patients deemed curable and productive, psychiatrists like Schottky simultaneously advanced the extermination of those considered unfit for therapy or unwilling to work.

Nevertheless, the use of electroshock therapy on Meta Bärwolf raises questions. The treatment was primarily used on people who had recently developed schizophrenia and were considered "acute cases" with good prospects of recovery. Meta Bärwolf, however, was already 68 years old in the fall of 1943 and had been institutionalized in Hildburghausen since 1927. Her medical file contains no justification for why she had to undergo this therapy at such an advanced age. It appears the sole reasons were her disruptive behaviour and her major agitation. Apparently, the use of such brutal treatments in Hildburghausen also served a socially disciplinary function. But the intended therapeutic effect seemingly failed to materialize, as Meta Bärwolf continued to be described as very restless even afterward. Remarkable in this context is the fact that Meta Bärwolf had to undergo surgery immediately following the treatment, during which nine teeth were extracted under anaesthesia. It cannot be stated with certainty whether this intervention was a direct result of the brutal shock treatment, during which dental damage can indeed occur.

What is striking, however, is that the physicians in Hildburghausen largely ceased their efforts to ensure the well-being of Meta Bärwolf after the failed shock therapy. It is likely that from this point onward, the medical and nursing staff even actively accelerated her death. Significant in this context is the fact that in the week prior to her death, the nursing report – also found in her medical file – noted a regular administration of both Luminal and Scopolamine. Both medications were used in the "Third Reich" not only as sedatives but also for the targeted killing of institutionalized patients. In Meta Bärwolf's case, the administration of these drugs led to her rapid death. She died on 30 November 1943 allegedly of "pneumonia." This diagnosis is characteristic of Nazi "euthanasia" and, together with the sudden onset of the illness, suggests that she may have been killed by medication. According to the autopsy report, she was also in a "severely reduced nutritional state."

This biography was written by Philipp Rauh.

© 2025 by Philipp Rauh, licensed under

CC BY 4.0

Source:

Staatsarchiv Meiningen, Bestand 4-62-304 (Fachkrankenhaus für Psychiatrie und Neurologie

Hildburghausen), Nr. 14603: Krankenakte Meta Bärwolf

Literature:

Faulstich, Heinz: Hungersterben in der Psychiatrie (1914-1949). Mit einer Topographie der

NS-Psychiatrie, Freiburg 1998.